“Far From Heaven” (2002) is Todd Haynes’s virtuosic homage to the cinema of Douglas Sirk (famous for “All That Heaven Allows” (1955) and “Imitation of Life” (1959).

“Far From Heaven” (2002) is Todd Haynes’s virtuosic homage to the cinema of Douglas Sirk (famous for “All That Heaven Allows” (1955) and “Imitation of Life” (1959).

The movie is a politicized melodrama brimming with detailed social commentary.

Haynes’s dynamic range of socially informed filmic storytelling is exquisite.

The context-rich narrative observes upper class mannerisms — private and public — native to the Eastern seaboard circa 1957. In Hartford, Connecticut children call their moms, “Mothers.” Ladies lunch.

Men work in lavishly modern wood-paneled offices of companies with names like “Magnatech.” The upper class views itself as “middle-class.”

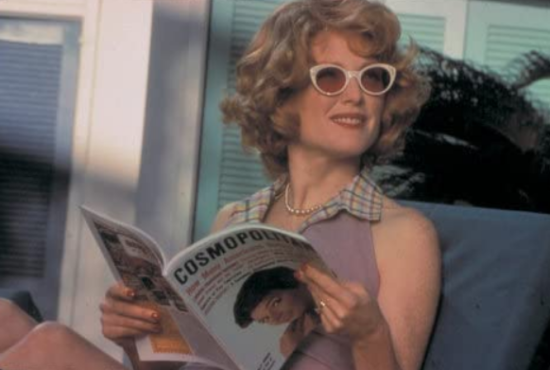

Dennis Quaid delivers a wonderfully understated reading as corporate family man Frank Whitaker. A closet homosexual, Frank engages in after-work trysts with other men. Frank’s doting wife Cathy (Julianne Moore) is a perfectly coiffed vision of ‘50s era motherly and wifely perfection.

Arrested for “loitering” in a movie theater, Frank’s secret life starts to unravel. Later, a spur-of-the-moment evening visit by Cathy to Frank’s corporate office — to deliver a homemade dinner — results in a shocking discovery. Regular visits to a psychiatrist promise to break Frank of his sexual addiction to other men.

Meanwhile, Cathy plays out her part as one of Hartford’s leading socialites. Her stylish well kept home, and her kindness toward “negroes,” becomes public record via a local magazine featuring the camera-friendly Cathy Whitaker.

Hayne’s perceptive scrutiny of an idyllic ‘50s era Right Wing American Dream draws a link between racism and anti-gay views, as well as between Hartford’s wealthy white suburbs and its black ghettos. The Whitakers have a black maid (Viola Davis) whose token status is lessened somewhat by the home’s mild gardener, Raymond Deagan (Dennis Haysbert).

A mutual attraction between Cathy and Raymond leads to an afternoon spent visiting a black restaurant in Raymond’s neighborhood. Witnessed together by one of the ladies-who-lunch, rumors about Cathy spread through her social circles. While Frank gets time off with a paid vacation for the family due to his crisis of personality, Cathy is forced to side with the racist status quo of her community. Even Cathy’s self-proclaimed best friend Ellle (Patricia Clarkson) shows her unreliable colors when Cathy speaks longingly of Raymond.

Douglas Sirk’s striking palate of saturated primary colors populates every frame of Haynes’s perpetually autumnal setting. The contrast of gritty dramatic material against an idealized — read fascistic — social atmosphere, makes for an enthralling movie experience. Cathy, Frank, and Raymond are socially repressed characters yearning for an earthy human connection different from what society deems acceptable.

The complex dramatic tapestry that Haynes crafts is as informative as the romantic tragedy is devastating. “Far From Heaven” is masterpiece of LGBTQ activist cinema. That it adheres to a classic cinematic model designed by one of the 20th century’s most visionary directors, allows for a special variety of dramatic transcendence for its audience. Heaven is not what it pretends.