Groupthink doesn't live here, critical thought does.

Welcome!

This ad-free website is dedicated to Agnès Varda and to Luis Buñuel.

Get cool rewards when you click on the button to pledge your support through .

Thanks a lot acorns!

Your kind generosity keeps the reviews coming!

Hailed by none other than François Truffaut as “the father of the French New Wave,” Roberto Rossellini’s cinematic influence grew out of the neorealist style he mastered while making his trilogy of anti-fascist World War II films, of which “Germany Year Zero” was the last.

Hailed by none other than François Truffaut as “the father of the French New Wave,” Roberto Rossellini’s cinematic influence grew out of the neorealist style he mastered while making his trilogy of anti-fascist World War II films, of which “Germany Year Zero” was the last.

All three films were made in the years immediately following the end of the war, and as such exhibit the fresh scars of wounds inflicted on landscapes and civilians alike — none more so than in “Germany Year Zero.”

In “Rome Open City” (1945) Rossellini examined the oppressive social climate in Rome during a period when the city suspended defensive efforts against the Nazi occupation in an effort to protect Italy's national treasures. “Paisan” (1946) employed six episodes, set in various Italian locations such as Florence, Sicily and Naples, to create a cumulative vantage point on the Italian wartime experience.

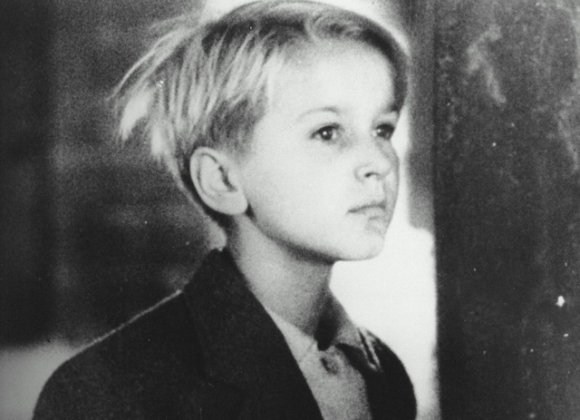

For the trilogy’s coup de grace Rossellini did the unexpected. He travelled to Berlin during the summer of 1947 to chronicle the effects of Germany’s defeat as witnessed through the eyes of a motherless 13-year-old German boy. Rossellini dared to provide a humanist look at the dreadful effects of World War II on Germany’s civilians. The recent death of Rossellini’s nine-year-old son Romano, during an emergency appendicitis surgery, played a key role in Rossellini’s choice to center the narrative on a young protagonist.

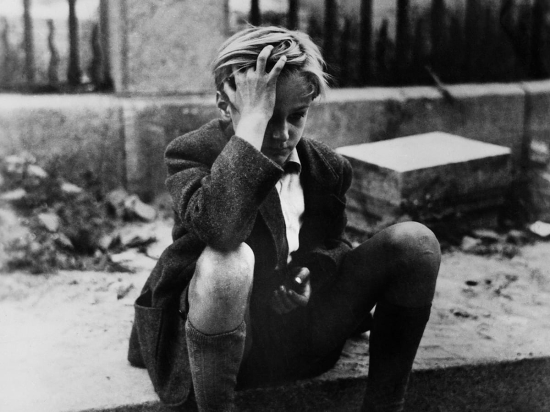

Berlin’s bombed-out streets set the film’s mood. Tons of rubble and overgrown weeds clutter every street for as far as the eye can see. Decked out in lederhosen, Edmund (Edmund Moeschke) is two years too young to obtain a permit for his temp job, digging graves for a few pieces of bread smeared with honey. His fellow German gravediggers expose Edmund’s lie for “not pulling his weight,” and he flees the cemetery. A few blocks away, Edmund begs for a piece of horsemeat being stripped from an equine corpse being cut open by the starving masses. He is denied.

At home, Edmund’s ailing anti-Nazi father wonders aloud if death might be better than the physical suffering he endures. Unable to assist the family, Edmund’s burdensome older brother Karl-Heinz (Franz-Otto Krüger) — a former Nazi military officer who fought to the bitter end — hides in their cramped apartment rather than turn himself in to be locked up as a prisoner-of-war.

At night, Edmund’s sister Eva flirts with American soldiers in cabarets in exchange for cigarettes and trinkets she can use to barter for food. It is up to Edmund to act like an adult and come up with creative ways to contribute to his family’s survival. During his travels, Edmund meets his former teacher Herr Enning, a Nazi pedophile whose sexual intentions are obscured in a speech he gives in response to Edmund’s request for food to help his father. "The weak are destroyed so that the strong survive,” he tells Edmund. “One must have the courage to let the weak die.”

Edmund’s interpretation of Herr Enning’s stern lecture sets up a fatalistic decision on the young boy’s part that leads to one of neorealist cinema’s most shocking yet inevitable climaxes.

Rossellini described realism as “nothing other than the artistic form of truth,” and here his quest for such authenticity refutes any idealized criteria of life-affirming value. In war, Rossellini seems to say, it is the innocent that suffer most.

Not Rated. 73 mins.