Groupthink doesn’t live here, critical thought does.

Welcome!

This ad-free website is dedicated to Agnès Varda and to Luis Buñuel.

Get cool rewards when you click on the button to pledge your support through .

Thanks a lot acorns!

Your kind generosity keeps the reviews coming!

Jean-Luc Goddard famously said, “French neorealism was born” with the cinema of Jacques Tati. At first blush, the statement might seem like an exaggeration, but there’s more than a little truth to it.

Jean-Luc Goddard famously said, “French neorealism was born” with the cinema of Jacques Tati. At first blush, the statement might seem like an exaggeration, but there’s more than a little truth to it.

A trained mime and music hall performer, Jacques Tati was a physically remarkable comedian who put his comic gifts to use as an opaque form of social commentary in a group of six films made between 1947 and 1971.

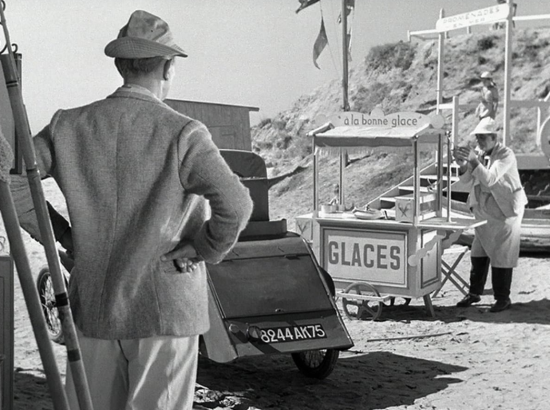

Tati’s painstaking sense of perfectionism is evident in his popular second film “Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday,” about a tennis enthusiast and fisherman on vacation in the idyllic French seaside village of Saint-Marc-sur-Mer.

Dressed in a comical hat, and walking with a distinctive forward-leaning gait, Tati’s tall alter-ego Monsieur Hulot represents a socially inept if well-meaning French everyman. Hulot’s ever-present raincoat, umbrella, and pipe conspire to put him in a class by himself. Monsieur Hulot haphazardly expresses his individuality as a symptom of his innate awkwardness.

The small convertible car that Hulot drives sputters loudly but it doesn’t bother our unflappable character. He is perfectly content with the things he has. He’s is a lover of jazz, something that aggravates guests at the hotel where Hulot stays when he sometimes blasts a jazz record near the lobby.

An early scene in “Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday” encapsulates Tati’s interest in conformity and social interaction. An eager group of people waits on a platform for the train that will take them to their vacation destination. A public address system announces that the next train will arrive on the opposite platform. The crowd vanishes into a stairwell before emerging from one on the opposite side. For a brief moment the scene is serenely devoid of anyone. Comically, a train arrives on the side the group has just abandoned. Again, they vanish to run back to their former place in order to catch the train that will transport them somewhere they can be free from the hassles of day-to-day living.

Like lemmings, once at their beachfront destination, the citizens move as an invisibly orchestrated group to place their umbrellas in the sand and copy one another’s movements. They act the same and therefore think the same. There is a tacit agreement that problems don’t exist on vacation.

An ingenious inventor of sight gags, Tati’s unique sense of humor pops during mundane moments. When Hulot attempts to straighten picture frames at the hotel, the fishing rod he holds inadvertently knocks others askew. Even something as simple as getting in a rowboat escalates into beach-clearing event when the boat that he accidentally breaks in half folds over to resemble a boxlike sea monster. Jacques Tati’s philosophical influence can be heard in the songs of Jonathan Richman. His comic set pieces inform Rowan Atkinson’s Mr. Bean character and Mike Myers’s Austin Powers spy-spoof franchise. There is an innocent nostalgia and precious regard for all things whimsical and romantic in the films of Jacques Tati. There is also a certain je ne sais quoi that is uniquely French.

Rated G. 83 mins.