Groupthink doesn’t live here, critical thought does.

Welcome!

This ad-free website is dedicated to Agnès Varda and to Luis Buñuel.

Get cool rewards when you click on the button to pledge your support through .

Thanks a lot acorns!

Your kind generosity keeps the reviews coming!

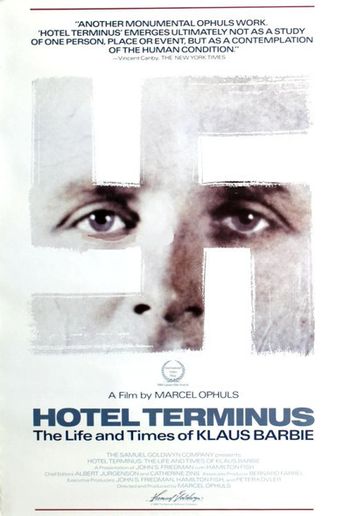

“Hotel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie” is an exhaustive documentary about the “Butcher of Lyon,” a notoriously sadistic Gestapo captain who personally tortured (many to death) more than a thousand French men, women, and children before being recruited by the CIA (then the “CIC” – the U.S. Army Counter Intelligence Corps) to assist with its campaign against socialists in Bolivia. Barbie liked to brag that it was he who “devised the strategy for murdering Ché Guevara.”

“Hotel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie” is an exhaustive documentary about the “Butcher of Lyon,” a notoriously sadistic Gestapo captain who personally tortured (many to death) more than a thousand French men, women, and children before being recruited by the CIA (then the “CIC” – the U.S. Army Counter Intelligence Corps) to assist with its campaign against socialists in Bolivia. Barbie liked to brag that it was he who “devised the strategy for murdering Ché Guevara.”

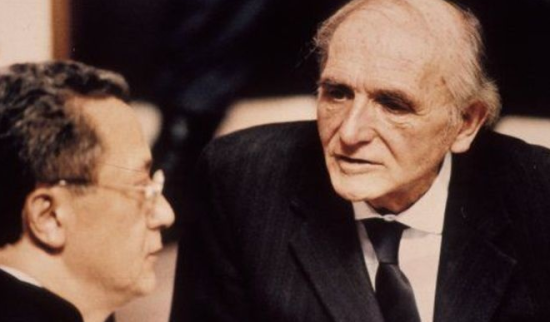

“Hotel Terminus” is a vigorous document made by a filmmaker (Marcel Ophuls) so hungry for satisfaction that every image and interview sequence spits with a personal sense of boiling outrage.

Ophuls edited the four-hour film down from over 120 hours of interview footage. The result is an alarming documentary because it exposes so much about inherent deceptions in 20th century political power structures, which have since come home to roost in the worst possible of ways in the 21st century. It is clear from events at Abu Ghraib, Guantánamo, and other U.S.-run prisons and blackout sites that the CIA studied and put into practice Barbie’s torture craft methods while applying them as standard operating procedures at home and abroad.

Marcel Ophuls (the Jewish son of the celebrated filmmaker Max Ophuls) made “Hotel Terminus” nearly two decades after completing “The Sorrow and the Pity,” an unrivaled filmic record of the collaborations between the Vichy regime and Nazi Germany during World War II. Together, the two films combine to form an essential micro/macro explanation (through first-person accounts and documented facts) of dark chapters in French and German history that would otherwise be kept mute. In “Hotel Terminus,” America and Italy (the Vatican in specific) are incriminated in the rampant skullduggery surrounding Klaus Barbie’s actions after his time spent carrying out Hitler’s Final Solution.

An often-repeated chorus of complaint comes from many French and Germans: Why does he [Ophuls], and so many others, insist on dredging up things that happened “40 years ago?” One such person exerts that there is a “20 year statute of limitations” on war crimes. (Not true.) The mitigation impulse elucidates how Hitler’s “criminal energy” spread from Germany to modern-day America. Ophuls interviews countless people connected to Barbie. Victims, neighbors, French collaborators, French resistance fighters, German colleagues, journalists, lawyers, American intelligence agents, and South American politicians relay their own impressions of Barbie. “He was a nice man” is a common refrain.

The emotionally devastating film draws to a close in 1987 when, at the ripe age of 73, Barbie’s sentencing in a French court to life imprisonment for “crimes against humanity” arrives as a meager footnote to justice. Sadly, “Hotel Terminus” is a bitter reminder that those in power will continue to abuse their authority with impunity knowing that even if they are caught there will be plenty of similarly dirty allies to protect them. Call it “the Klaus Barbie effect.”