Savoring von Trier

The Best Horror Film of the Last 30 Years

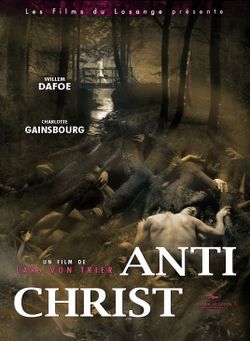

By Cole Smithey

Lars von Trier is a true poet of cinema. He has a painterly eye for

composition –formal, surrealistic, and radical. In a natural setting

of a remote cabin named Eden hidden deep in the woods of the Pacific

Northwest, von Trier scorches his mark with one of the most shocking

horror films of the past 30 years. The Danish filmmaker creates a tense

and provocative collage of death, brutality, psychotherapy, sexual

desire, and the fury of Mother Nature. A symphony of simultaneous

madness afflicting the females of various species of animals parallels

the mental deterioration of a wife (Charlotte Gainsbourg) after the

death of her son–who fell out a window while the couple was making

love. Dafoe, as her therapist husband, tries to head off his wife's

teetering nervous breakdown with therapy exercises and goal-oriented

games that amplify her fear of staying at Eden. His insistence that

they go on the retreat to face her fears and heal her leads to all

sorts of symbolically evil events that surround Gainsbourg as a

sexually aggressive and violent wife.

Von

Trier toys with implying an archetypal status to the husband, referred

to only as "He," and Gainsbourg's character, credited as "She." "He" is

a logical person, who substitutes the remorse he feels for the loss of

his child with curing his deeply disturbed wife even if such an effort

contradicts ethical concerns for his professional duty as a

psychoanalyst that would prevent him from treating a member of his own

family. "She," on the other hand, places importance on sex as a way of

distancing herself from the result of the activity that was responsible

for bringing her son into the world and for inadvertently casting him

out.

After

After

its press screening at the New York Film Festival, I asked von Trier

about the implications of the film's biblical references, such as

naming the couple's isolated retreat "Eden" and an oblique reference to

"Satan." The candid filmmaker replied that if anything it was to reject

the existence of God. Von Trier has publicly discussed his battle with

depression that led to writing "Antichrist" as a kind of self-therapy

before filming the movie with a lazy approach that took full advantage

of employing free association to add or augment scenes. The auteur

sites Strindberg as an influence, and you can recognize it in von

Trier's formal distillation of social and personal ideas. "Antichrist"

is broken into three stages, "Grief," "Pain," and "Despair." But the

terms play so loosely with the action of each act that the superseding

action on display challenges the audience to equate the horrors

on-screen with traumatic events in their own lives.

Like

Luis Bunuel, von Trier works from a rich subconscious narrative

landscape where adult fears and fantasies are played out beyond their

illogical parameters. Where a film like "The Exorcist" works on a

corollary algorithm pitting good against evil, von Trier embraces the

cruelty of nature, with its psychological frailty and physical

vulnerability pressed hard to the fore. That he does so within an

intimate romantic context that calls into play furious aspects of

sadomasochistic sexuality that fire the film into an area of implacable

volatility.

"Antichrist"

is a demanding film that pushes its dark ideas and exaggerated

situations through a dialectic of carefully guided precepts. As with

Alfred Hitchcock, Lars von Trier deploys a direct cinematic language

that allows the audience to trust in his mastery of filmic art, as well

as his ability to gross them out without breaking their confidence. Von

Trier is a master filmmaker. His exploration into the genre of horror

has given us a film far more frightening than anything Hollywood would

ever allow. As with all of von Trier's films, there's some Dogme for

the audience to chew on. If "Antichrist" is the "most important film of

von Trier's career," as he has stated, then there is all the more

reason to savor it.

(IFC Films) Rated R. 109 mins. (A) (Five Stars)