Groupthink doesn’t live here, critical thought does.

Groupthink doesn’t live here, critical thought does.

Welcome!

This ad-free website is dedicated to Agnès Varda and to Luis Buñuel.

Get cool rewards when you click on the button to pledge your support through .

Thanks a lot acorns!

Your kind generosity keeps the reviews coming!

Arthur Penn’s recounting of the story of Bonnie and Clyde — two of America’s most iconic outlaws — is a seamless balancing act. Equal parts true-crime exposé, dysfunctional love story, and Depression-era think piece, the picture underscores American police departments’ longstanding proclivity for short cuts to justice, i.e. murder.

Arthur Penn’s recounting of the story of Bonnie and Clyde — two of America’s most iconic outlaws — is a seamless balancing act. Equal parts true-crime exposé, dysfunctional love story, and Depression-era think piece, the picture underscores American police departments’ longstanding proclivity for short cuts to justice, i.e. murder.

For all of the critical noise made over Penn’s methodical slow-motion hail of bullets massacre of Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker at the hands of a small-town sheriff, the extended sequence of outrageous violence speaks volumes about the systemic corruption of America’s policing system. The bloody conclusion comprises the ethical essence of the film. As with the sad fate of many other millions of guilty and innocent U.S. citizens, Bonnie and Clyde were not afforded due process of law.

“Bonnie and Clyde” was released in 1967, two years before Sam Peckinpah’s “The Wild Bunch” employed an even more exaggerated, and controversial, climax of slo-mo bloodshed for its exiled hero cowboys. Film critics like Roger Ebert were quick to associate “Bonnie and Clyde” with the French New Wave — vis-à-vis François Truffaut’s “Jules and Jim” — but Ebert and his ilk were reaching. Stylistically, Penn’s film shares little in common with Truffaut’s film, and even less with Jean-Luc Godard’s outlaw genre effort “Breathless.”

The fact that Truffaut introduced David Newman’s script for “Bonnie and Clyde” to Warren Beatty, the film’s future producer-and-lead-actor, had little to do with any direct influence from the Nouvelle Vague. Arthur Penn’s background in historic socially relevant dramatic material, on the other hand, meant a lot.

After directing stage plays in wartime Britain, Penn’s first film (“The Left Handed Gun” – 1958) was about the Old West outlaw Billy the Kid. Starring a young Paul Newman as William Henry McCarty (a.k.a. Billy the Kid), and based on a script by Gore Vidal, the apparent Western presented a thinly veiled social analysis about corrupt sheriffs.

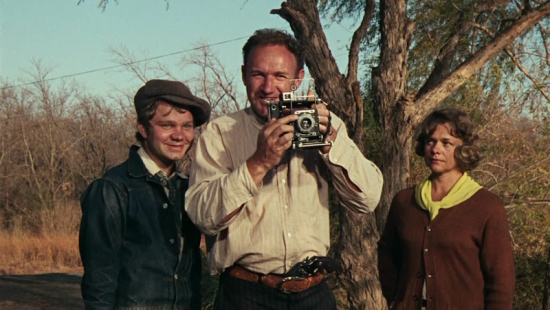

The grudge-carrying sheriff responsible for orchestrating the ambush that left Bonnie’s and Clyde’s bodies and car riddled with dozens of bullet holes, acted out his resentment over a photograph that the robber duo posed with him at gunpoint, before sending it to a local newspaper.

Penn sets the Depression era’s hopeless condition in the forefront of the narrative. Clyde robs gas stations, stores, and banks because it’s the most expedient way he knows to make money in a society with few other options. He meets Bonnie whilst attempting to steal her brother’s car. Their mutual attraction is tempered by Clyde’s impotence; he may be a homosexual, closeted even to himself. Warren Beatty’s embrace of his character’s lack of sexual prowess adds significantly to explaining Clyde’s bravado and hunger for criminal fame. Clyde likes to announce, “We’re the Barrow Gang” before robbing a bank.

Faye Dunaway’s earthy portrayal of Bonnie, a small town beauty queen worthy of a greater fate than working all of her days as a diner waitress, answers the film’s burning questions about how and why Bonnie took up a life of crime with a man who couldn’t even fulfill her sexual needs. Arthur Penn uses the poem Bonnie writes telling hers and Clyde’s story as a grounding centerpiece for the story. Bonnie had brains to back up her beauty, but America’s dire social conditions provided her with no outlet for her potential to make a “sensational break.”