May 23, 2015 CANNES — The over-booked midnight screening for “Love” (Argentinian enfant terrible Gaspar Noe’s latest provocation) caused at least one fistfight to break out in front of the Palais last night. Those ticketed audience members that did get inside the crowded auditorium were treated to one of the biggest examples of regression for any filmmaker in recent history. What a flop. Pornographic in nature, “Love” is a 3D sexploitation movie made by a filmmaker unaware of the genre that he’s working in. Noe, the genius behind such groundbreaking cinematic examples of social satire as “I Stand Alone” and “Irreversible” has made a film so sophomoric that it boggles the mind that it came from the same person who made “Enter the Void,” one of the most visually and viscerally challenging films of the last 20 years.

May 23, 2015 CANNES — The over-booked midnight screening for “Love” (Argentinian enfant terrible Gaspar Noe’s latest provocation) caused at least one fistfight to break out in front of the Palais last night. Those ticketed audience members that did get inside the crowded auditorium were treated to one of the biggest examples of regression for any filmmaker in recent history. What a flop. Pornographic in nature, “Love” is a 3D sexploitation movie made by a filmmaker unaware of the genre that he’s working in. Noe, the genius behind such groundbreaking cinematic examples of social satire as “I Stand Alone” and “Irreversible” has made a film so sophomoric that it boggles the mind that it came from the same person who made “Enter the Void,” one of the most visually and viscerally challenging films of the last 20 years.

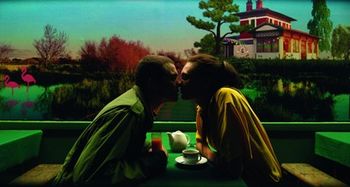

Presented as Noe’s dream-project since his early days in film school, “Love” is meant to display the reality of “sentimental sensuality” via “blood, tears, and cum.” However, semen is by far the most plentiful of the three fluids shown on, and off-screen, when you consider the graphic scene in which Noe takes obvious advantage of the 3D process to break the proscenium window.

Featureless no-name actor Karl Glusman plays the director’s younger alter ego Murphy, an ever-horny American studying filmmaking in Paris. Murphy (yes "Murphy's law is the trite allusion that Noe is compelled to spell out in block letters) is an eternally miserable soul whose passion for cinema means that he wears an olive-green Army jacket just like the one Robert De Niro wore as Travis Bickle in “Taxi Driver.” Posters from such controversial films as “Salo” and “Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein” adorn Murphy’s small Parisian pad that he shares with Omi (Klara Kristin) the mother of his son Gaspar, thanks to a broken condom. Not only is there not a single empathetic character in the movie, but also the ostensibly character-defining, formally explicit sex acts that Noe films primarily from above, illuminate fewer aspects of personality traits than you would find in a typical sample of homemade porn.

Featureless no-name actor Karl Glusman plays the director’s younger alter ego Murphy, an ever-horny American studying filmmaking in Paris. Murphy (yes "Murphy's law is the trite allusion that Noe is compelled to spell out in block letters) is an eternally miserable soul whose passion for cinema means that he wears an olive-green Army jacket just like the one Robert De Niro wore as Travis Bickle in “Taxi Driver.” Posters from such controversial films as “Salo” and “Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein” adorn Murphy’s small Parisian pad that he shares with Omi (Klara Kristin) the mother of his son Gaspar, thanks to a broken condom. Not only is there not a single empathetic character in the movie, but also the ostensibly character-defining, formally explicit sex acts that Noe films primarily from above, illuminate fewer aspects of personality traits than you would find in a typical sample of homemade porn.

Traditionally, Cannes includes at least one salacious movie in every festival. In 2003, Vincent Gallo’s “The Brown Bunny” sent critics groaning over its gratuitous oral sex scene between Chloe Sevigny and Gallo. “Brown Bunny” certainly isn’t any better than “Love” but it was mercifully shorter at 93 minutes as compared to “Love’s” arduous running time of 130 minutes. Another difference is that no one expected much from Vincent Gallo as a filmmaker, who had only made one film (“Buffalo 66”) before “Brown Bunny.” The situation is considerably different for Noe who is likely to find that even his staunchest supporters will find little to admire, much less love, in a film that seems more like a student film project than a movie from an experienced filmmaker.

Although inappropriately screened in the Cannes Classics section of the festival Kent Jones’s painstaking documentary, about the historic eight-day interview sessions between Francois Truffaut and his hero-filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock fulfills an essential niche in the history of cinema. The interviews, for which Truffaut carefully planned for in advance in the same way that he would prepare to make a film, approached each of Hitchcock’s films up to that point, in chronological order. The resulting book (“Hitchcock Truffaut”) became a touchstone for several generations of filmmakers, such as Olivier Assayas, David Fincher, Richard Linklater, and Paul Schrader — both of whom are interviewed in the documentary.

The weakest link of the modern-day filmmakers that Jones includes for commentary is notorious art-house hack pretender James Gray, whose inclusion alongside the likes of Martin Scorsese hits a wrong note. That said, “Hitchcock Truffaut” makes ample use of clips from the films of both directors to explicate the methods and cinematic language each used toward telling stories on film. The effect is magical as it is informative. Seamlessly narrated by Bob Balaban’s non-imposing voice-over, the documentary walks a neat line between pedagogy and entertainment. The only danger is that the viewer may feel inspired to go on an Alfred Hitchcock bender after seeing it.