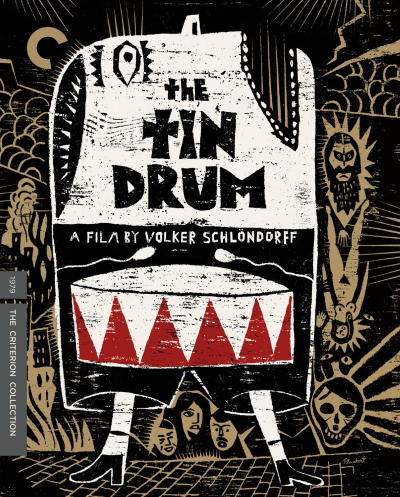

Context is everything. Though often mistaken as a black comedy, Volker Schlöndorff’s audacious reworking of Günter Grass’s abstractly autobiographical 1959 novel is an exemplary model of European magical realist cinema.

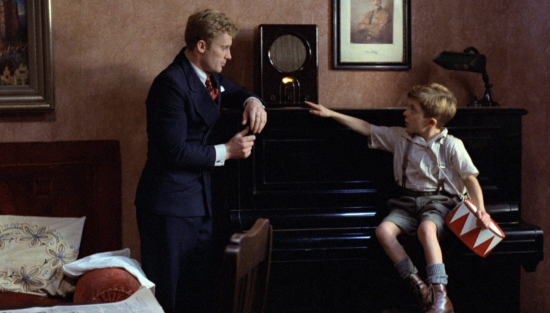

The first of Grass’s “Danzig Trilogy” is set from World War I through World War II in Poland’s free city of Danzig, which is invaded by Nazi Germany. The picaresque narrative is one of surreal emotional and psychological displacement as seen through the eyes of a ferocious child. The young unreliable protagonist Oskar (David Bennet) is one of the most enigmatic, if tormented, characters in all of cinema.

In the face of the volatile wartime situation that surrounds him, the three-year-old Oskar — “anchored between wonder and illusion” — throws himself down a flight of stairs in his parents’ grocery store apartment in order to deliberately stunt his growth. From that moment on, Oskar’s mind and inner physiology develop but his body does not. He is an impish boy with feral eyes set in an oversized head. Oscar’s mother compensates for her child’s bizarre condition by providing him with a lacquered red-and-white tin drum that she constantly replaces as he recurrently breaks them over time.

The bright drum that perpetually hangs on a rope from his shoulder is an effective symbol of Oskar’s manic individuality and of his self-appointed position as a mascot for the multicultural pressure cooker of Danzig. The city is populated with German civilians, Jews, Kashubians, Nazi soldiers, and Poles. Oskar is a gifted drummer after all — a talent revealed when he sits under a bandstand playing syncopated counter-rhythms to those of a Nazi military band.

Yet, Oskar’s greatest defense mechanism, alongside his concealed maturity, is his alarming ability to break glass with the sound of his shrill yell. However charismatic Oskar’s outward appearance, his demonic alter ego presents an effective warning to society at large that he is not to be messed with. Oskar’s sparse narration fills in significant exposition about his disguised maturity. Oskar says, regarding a Nazi building-burning attack on synagogues and Jewish businesses, “Once upon a time, there was a gullible people who believed in Santa Claus. But Santa Claus was really the gas man!” The murder of the Jewish toyshop owner (Charles Aznavour) who sold Oskar’s trademark drums comes with a poignant sense of loss.

The casting of an 11-year-old David Bennet in an otherwise insurmountable role is the key to the film’s success. Half a boy, and half a man, Bennet’s ingeniously steely portrayal efficiently

every pigeonhole that Grass’s outré plot offers up. When Oskar makes love to his father’s teenaged housekeeper, the exchange of corporeal affection momentarily replaces the sickening mood of obsequious Nazi propaganda and familial loss that Oskar endures with detached stoicism.

Oskar survives while those around him perish. However efficient the Nazi war machine, Oskar outsmarts his desperate situation. He is a refugee hero. Oskar’s will to live eclipses all else. It is something that he, and only he, controls.

Rated R. 142 mins.