Widely trashed by a cabal of critics who didn’t know a good film when they saw it, Jack Clayton’s 1974 adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel beautifully captures its romantic essence and caustic social indictments. The film’s only misstep is in wearing out Irving Berlin’s repurposed ballad “What’ll I Do” to distracting effect as an over-repeated aural motif.

Widely trashed by a cabal of critics who didn’t know a good film when they saw it, Jack Clayton’s 1974 adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel beautifully captures its romantic essence and caustic social indictments. The film’s only misstep is in wearing out Irving Berlin’s repurposed ballad “What’ll I Do” to distracting effect as an over-repeated aural motif.

Roger Ebert’s review at the time of its release disparaged the film for being “faithful to the novel with a vengeance,” yet not staying true to the book’s “spirit.” You can’t have it both ways. The film is loyal to Fitzgerald’s complex story — as adapted by Francis Ford Coppola in screenwriting mode. Which is saying a lot.

“The Great Gatsby” is about a cataclysmic shift in American society, as well as in the mindsets of people unable to compensate for the shifting sociocultural ground occurring under their feet. Every character suffers from some form of self-delusion — Jay Gatsby being the worst offender. That the fragile female object of Gatsby’s deeply rooted desires isn’t worthy of his blind devotion is beside the point…well, his point, anyway. He just wants to recreate the past at all cost, regardless of how intrinsically impossible the endeavor.

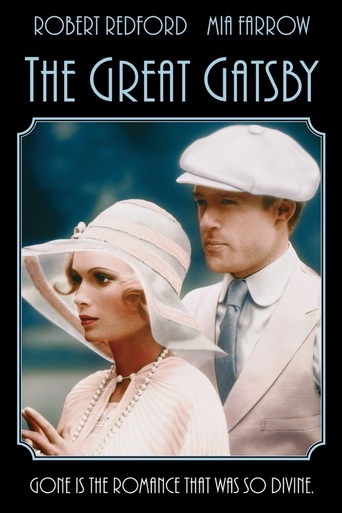

Our reliable narrator Nick Carraway (wonderfully underplayed by Sam Waterson) is financially impotent, yet shares none of the greed that his well-off cousin Daisy Buchanan (Mia Farrow) imposes on her skewed value system. Nick lives in a cottage across the “lawn” from Gatsby’s mammoth estate on Long Island.

Late in the story Nick describes Gatsby’s “extraordinary gift for hope – a romantic readiness such as I have never found in any other person.” Nick’s blind admiration for Jay Gatsby mirrors Gatsby’s conclusive attraction to Daisy. Having falling for Daisy when he was on leave during World War I, Gatsby quickly amassed a fortune “in the drugstore business” in order to land Daisy as his wife. Still, enough time passed for Daisy to be swept off her feet by Tom (Bruce Dern), a millionaire without an honorable bone in his body — much less a romantic one.

Gatsby’s waterfront mansion sits across the bay from Tom and Daisy’s home, which they share with their six-year-old daughter. At his own expense, Gatsby has installed a green beacon in the bay in front of Daisy’s home so he can draw a visual bead on her location. The film is rife with significant visual markers that Fitzgerald included to guide his readers. The attention to detail in the film is meticulous. The famous “shirt scene” from the book provides a galvanizing moment of romantic fulfillment in the movie. Adoration of opulence equals sex.

Robert Redford’s Gatsby is a self-made man who utilizes his romantic obsession to achieve his capitalist conquest though shady means. Once attained, he has little use for his riches except to secure Daisy’s validating love. Gatsby understands too well Daisy’s steadfast opinion that “rich girls don’t marry poor boys.” What Gatsby—a stand-in for the rising robber-baron capitalism of his time—and ours—refuses to realize is that Daisy’s attitude is a symptom of a corrupt value system that no amount of money or love can overcome.

Rated PG. 144 mins.