Groupthink doesn’t live here, critical thought does.

Welcome!

This ad-free website is dedicated to Agnès Varda and to Luis Buñuel.

Get cool rewards when you click on the button to pledge your support through .

Thanks a lot acorns!

Your kind generosity keeps the reviews coming!

Italian poet, novelist, philosopher, filmmaker, blasphemer, Marxist, Catholic, communist, homosexual, and atheist are some of the titles that frame Pier Paolo Pasolini’s complex nature.

An escaped refugee of Catholic indoctrination, Pasolini’s disciplined poetic sensibilities guided his expression as a filmmaker to transcend global culture’s hypocrisy of ideologies. Pasolini was foremost a fearless commentator on culture able to simultaneously attack and embrace subjects such as communism.

During a planned visit with Pope John XXIII in 1962, in Assisi, to discuss the church’s relationship with non-Catholic artists, Pasolini chose to adapt the Gospel of Matthew, about Jesus’s path to crucifixion and resurrection.

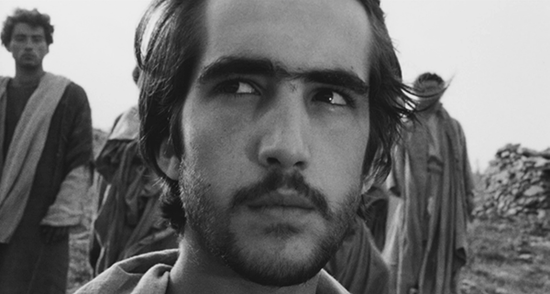

Pasolini’s use of Italian non-actors develops the black-and-white film’s neorealist approach with an authentic sense of biblical reality realized in the distinctive faces of the peasant community. Even the 19-year-old actor (Enrique Irazoqui) who plays Jesus Christ was a Spanish economics major that Pasolini transformed into the world’s most famous martyr. Much of the film contains close-up shots of Irazoqui speaking the eloquent poetry of Jesus’s teachings. Pasolini’s camera cuts between Irazoqu’s forcefully spoken lines; the natural atmosphere switches between dark and light, and between anger and peacefulness.

Pasolini humanizes Jesus to the point that the spectator is allowed to see beyond the inherently preachy nature of the story, and view Jesus in a modern day context. Certainly anyone acting and speaking — as Jesus did — would meet the same fate regardless of what era they inhabited. The audience is able to study the religious propaganda as a fictional parable where the things the authors took for granted announce themselves by omission.

Witnesses sob while Roman soldiers impale and crucify Jesus, an ostensibly insane person intent on self-destruction. Pasolini creates space for questions arise. If the crowd cares so much for Jesus, why don’t they overtake the handful of soldiers that murder their hero?

The film’s prolific music director Luis Bacalov creates a groundbreaking score that draws on sacred music from different cultures. Bach (Mass in B Minor), a borrowed track from “Alexander Nevsky,” blues (“Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child”), Jewish heritage (“Kol Nidre”), and Congolese (“Missa Luba”) are some of the curated pieces that Bacalov uses to create the film’s subtext-rich soundscape.

Pasolini’s films are natural cousins to Luis Buñuel’s surrealist works. Both filmmakers made movies with equally straightforward cinematic approaches to addressing social truths. Thematic subtext breeds in a frame where nothing can hide. This film seems to say that religious doctrine has worked as long as it has because its poetry is so beautiful. It also allows for the passing of generations who will eventually reject all religion because it is ultimately a lie.