Groupthink doesn’t live here, critical thought does.

Welcome!

This ad-free website is dedicated to Agnès Varda and to Luis Buñuel.

Get cool rewards when you click on the button to pledge your support through Patreon.

Thanks a lot acorns!

Your kind generosity keeps the reviews coming!

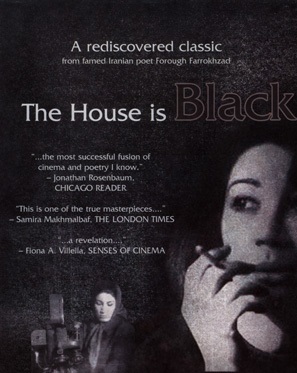

The alternately celebrated and controversial (once banned) Iranian feminist poet Forough Farrokhzad (1935-1967) made only one film in her short lifetime. “The House is Black” (1962) is a haunting transgressive documentary that uses a combination of poetry and facts to reveal the humanity hiding beneath the disfigured faces and bodies of impoverished lepers living in the Behkadeh Raji leper colony in Tabriz.

Farrokhzad’s words advise us:

“There is no shortage of ugliness in the world.

If man closed his eyes to it, there would be even more.

But man is a problem solver.

On this screen will appear an image of ugliness…

a vision of pain no caring human being should ignore.

To wipe out this ugliness and to relieve the victims…is the motive of this film and the hope of its makers.“

Framing the film as a humanitarian appeal, coming from a social activist, casts a layer of socio/political import over the proceedings, which Farrokhzad narrates in a soothing voice.

A leper peeks into a mirror through the scarf that she wears to mask her heavily scarred face. A classroom of leper boys read aloud from a book, thanking God for blessings such as “hands to work with,” and “eyes to see the marvels of this world.” A brutal ironic subtext seethes within Farrokhzad’s fearless close-up framing of young deformed men who will never enjoy such luxuries as travel. The boy praising the glory of hands holds his book with frozen gnarled lumps of bone and flesh. This is human suffering at its most excruciating.

Farrokhzad informs the audience about the curable physical condition of leprosy. Doctors describe the effects of the condition on the disfigured patients they treat before the camera. The film is in part a medical document. The filmmaker also creates a scathing castigation of social and political neglect for people in dire need of medical and therapeutic treatment.

At just 22 minutes, “The House is Black” accomplishes the work of much longer documentaries. Rough editing creates a shorthand style of cinema vérité.

A woman with hardly any fingers on her hands nurses her baby.

Farrokhzad’s poetry editorializes on the troubled lives at hand.

“Remember that my life is wind

I have become the pelican of the desert,

The owl of the ruins

And like a sparrow I am sitting alone on the roof

I am poured out like water

As those who have long been dead.

On my eyelids is the shadow of death

Leave me, leave me,

For my days art out of breath

Leave me before I set out

For the land of no return

The land of infinite darkness”

We savor a long shadow cast by a little girl at play dragging a shovel. Forough Farrokhzad finds hope in such long shadows.

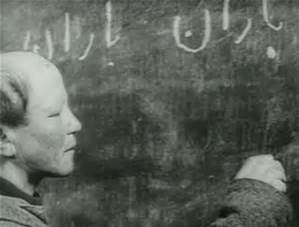

When asked to write a sentence on the blackboard with the word “house” in it, a student with leprosy who looks much older that his years takes a piece of chalk and writes, “The house is black.” So it is.

Not Rated. 22 mins.