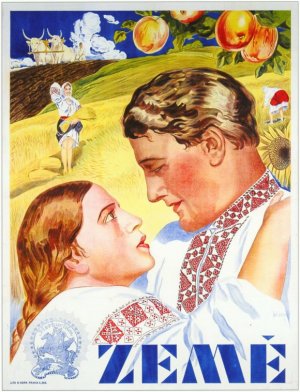

Alexander Dovzhenko’s controversial 1930 silent film “Earth” (“Zemlya”) was the last of his “Ukraine Trilogy” (following “Zvenigora” and “Arsenal”). Having fought for the short-lived nationalist Ukrainian People’s Republic against the Soviet Union’s Red Army at the age of 25, and serving time in a NKVD concentration camp, the 36-year-old Dovzhenko judiciously chose to utilize Ukrainian soil as the neutral protagonist for a film that on first blush seems to be a confused piece of political propaganda.

Alexander Dovzhenko’s controversial 1930 silent film “Earth” (“Zemlya”) was the last of his “Ukraine Trilogy” (following “Zvenigora” and “Arsenal”). Having fought for the short-lived nationalist Ukrainian People’s Republic against the Soviet Union’s Red Army at the age of 25, and serving time in a NKVD concentration camp, the 36-year-old Dovzhenko judiciously chose to utilize Ukrainian soil as the neutral protagonist for a film that on first blush seems to be a confused piece of political propaganda.

However, Dovzhenko’s depictions of political and religious idolatry, germane to the region at the time, serves as a violent counterpoint to the peaceful Earth, which will endure long after such manmade artificial constructs as borders and ideology are long gone. Although condemned as a “counterrevolutionary” film, “Earth” is a picture that mocks political and religious rhetoric through a brilliant use of montage techniques to unify disconnected events and emotions.

The location is a small Ukrainian village coming to grips with an era of Soviet-enforced collectivization in which commissars seized 2.5 million tons of grain after an enormous shortfall. Under Stalin, private land that hand been passed down for generations by “Kulaks” (under a Tsar’s rule dubbed “rural capitalism”) was consolidated under Soviet control in order to resolve the grain shortages.

Stalin also employed technology, in the form of gas-run tractors, one of which promises to improve the lives of the peasant farmers that bring the modern machine to life by filling its empty radiator with their urine.

The all-encompassing social narrative starts with the death of Simon, a grandfather whose serene death, in the company of his family beneath a pear tree, stands at stark comparison to the eventual murder of his grandson Basil at night by anti-collectivization agitators, i.e., wealthy farmers. The untimely death of his son drives Basil’s disconsolate father to publically declare his atheism and demand that his fellow villagers assert their newfound liberation by conducting Basil’s funeral without “priests and parsons.”

The filmmaker creates a procession climax of splintered realities. Basil’s distraught fiancée throws a nude tantrum in her bedroom; the local priest calls to the heavens for God to smite the villagers; Basil’s killer yells an admission of guilt that is drowned out by an orator who seizes the opportunity to promote the idea of collectivization. He says, “The glory of our Basil will fly all around the world like that Communist airplane of ours up there!”

When viewed as a social satire disguised as poetic social realism, “Earth” takes on a unique quality. The film confused many Soviet authorities unable to discern Dovzhenko’s invisible political angle, while the Red Army officially endorsed it. By hiding his cynicism inside a film that celebrates nature with groundbreaking visual and editing techniques Dovzhenko subversively created a regionally political film that could play to international audiences. “Earth” is widely revered as a cinematic masterpiece even if many who tout its worth don’t understand the polemic.

Not Rated. 75 mins.